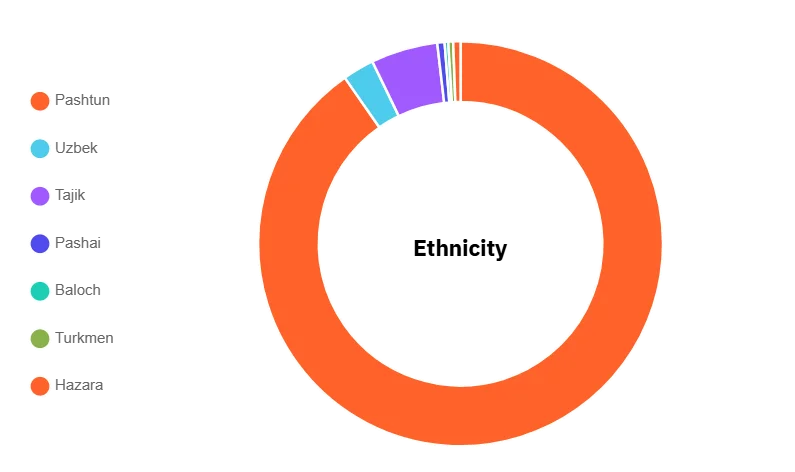

Afghanistan is inherently multiethnic. Tajiks, Hazaras, Uzbeks, Turkmens, Aimaqs, Baloch, Nuristanis, and a host of smaller groups share the same geography with Pashtuns, who form a large and politically influential community. This ethnic plurality has shaped Afghan politics for two centuries. Yet the configuration of power since 2021 has highlighted a worrying imbalance: the interim regime that now governs Kabul is overwhelmingly drawn from a single ethnic base, with profound implications for legitimacy, stability, and national reconciliation.

Afghanistan’s plural social fabric

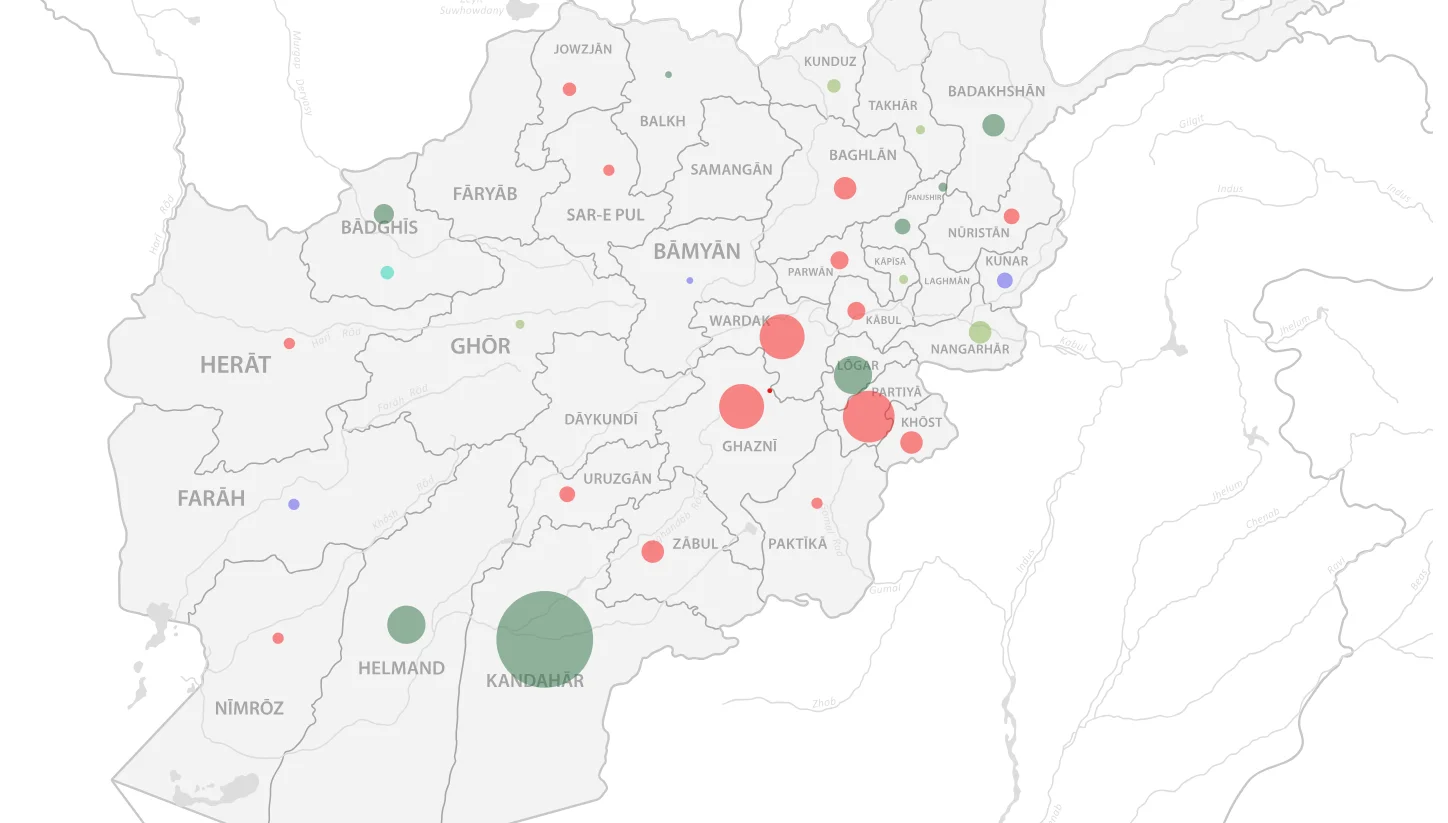

Ethnic identity in Afghanistan is not merely academic. It structures language, local governance, patronage networks, and historical grievance. Tajiks dominate much of the north and urban professional classes; Hazaras are concentrated in the central highlands and have distinctive cultural and religious identities; Uzbeks and Turkmens have regional strongholds in the northwest; Pashtuns are concentrated in the south and east and historically supplied much of the country’s rural leadership. For any state that aspires to durable rule, political arrangements must reflect this pluralism in both personnel and policy.

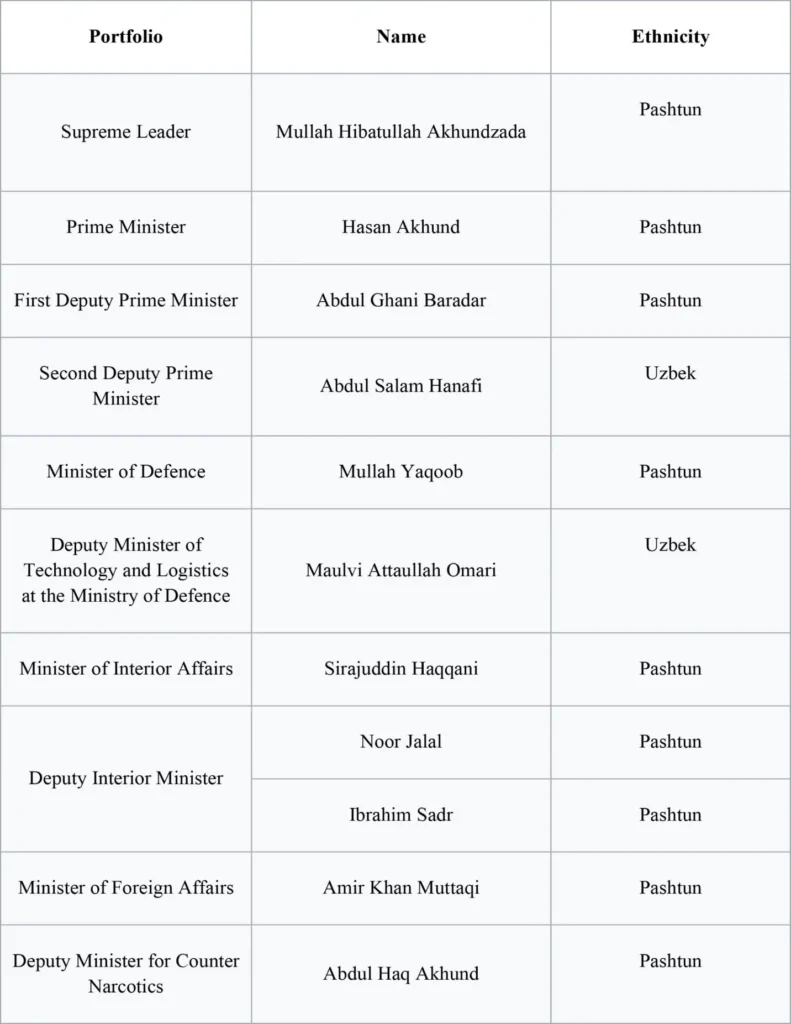

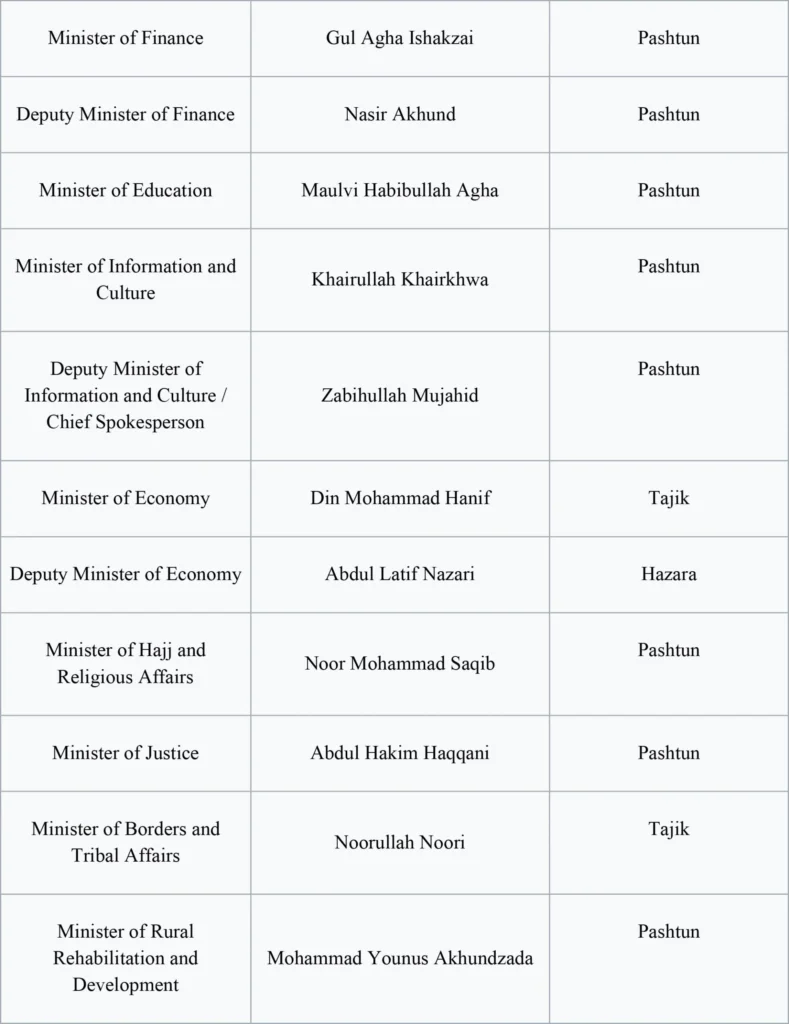

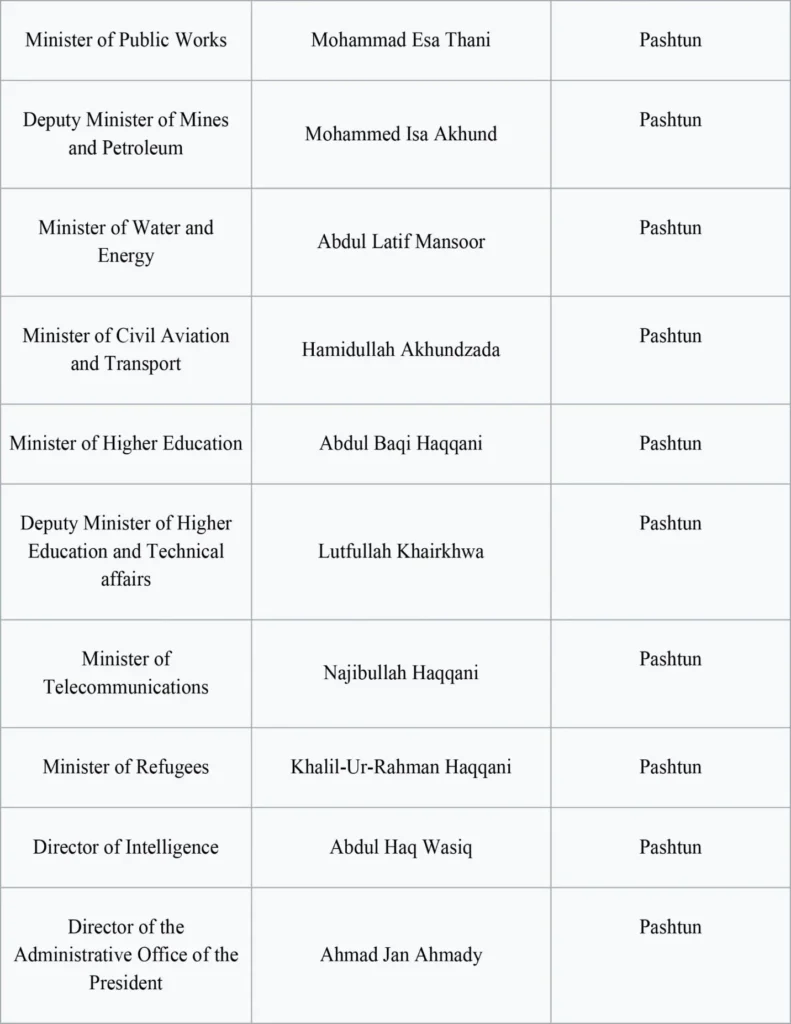

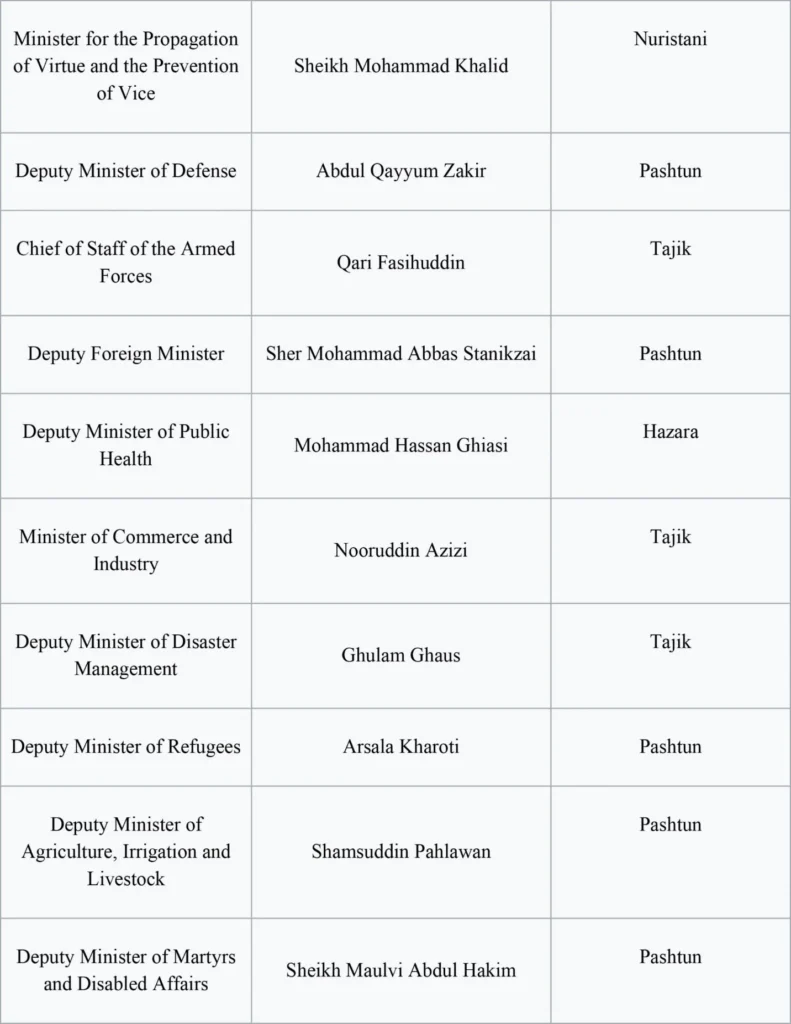

Leadership composition of the interim regime

Since the Taliban’s return to power, the composition of the senior leadership and the most visible ministries has been heavily skewed toward Pashtun backgrounds. The supreme leadership and the core religious-military council, the senior political officeholders (including the de facto prime minister and several key ministers), as well as many provincial governors and security commanders, trace their social roots to Pashtun-majority regions in the south and east. Prominent figures widely identified with the movement emerged from Pashtun districts and Taliban recruitment heartlands, and their promotions reflect the movement’s internal hierarchies and battlefield loyalties.

This concentration is not accidental. The Taliban grew out of Pashtun-dominated areas, and its networks of kinship, madrassa ties, and local patronage naturally elevated individuals from those communities into the movement’s command structure. When insurgent organizations convert power into governance, the initial distribution of authority tends to mirror the insurgency’s recruitment geography, and in this case, that meant a strong Pashtun predominance.

Consequences of ethnic dominance

When political authority clusters within one ethnic group in a multiethnic country it creates structural exclusion. Non-Pashtun communities, Tajiks in the northeast and west, Uzbeks in the north, and Hazaras in central Afghanistan, view appointments that neglect their representation as evidence of a project that seeks consolidation rather than reconciliation. That perception fuels alienation and weakens the social contract.

Practically, the ethnic tilt manifests in governance choices: security approaches shaped by experiences on Pashtun frontlines; centralized decision-making reflecting movement loyalty rather than inclusive consultation; and limited space for political actors outside the movement’s networks. Minority communities experience the effect as reduced access to decision-making, fears over cultural and political marginalization, and a sense that local grievances will be subordinated to a uniform national agenda driven by movement priorities.

The Taliban as an undemocratic political actor

Beyond ethnicity, the movement’s internal political culture compounds the problem. The Taliban’s decision-making is hierarchical, opaque, and rooted in religious-military command. Power is concentrated in a narrow group of senior leaders who enforce ideological conformity and reward loyalty over merit or electoral legitimacy. There are no mechanisms for broad-based political contestation, nor are there institutions guaranteeing minority rights or protected participation. In short, the interim regime lacks the democratic instruments, elections, representative institutions, and transparent appointments that would reassure diverse communities that their interests matter.

This character explains why the regime has struggled to win broad-based legitimacy. Domestic inclusion cannot be achieved through token appointments alone; it requires institutional guarantees and visible power-sharing that reach down to provincial and local levels. The movement’s governance model prioritizes control and unity within its ranks over the messy compromises of plural politics.

Paths to a more inclusive settlement

If Afghanistan is to achieve durable stability, the interim regime must address both ethnic imbalances and the non-democratic nature of its political system. That requires several tangible shifts: meaningful representation. Senior national and provincial posts should reflect the country’s ethnic diversity in ways that give real authority, not mere symbolism.

Institutional guarantees: Constitutional or quasi-constitutional protections for minority rights, language, and local autonomy would help reduce fears of marginalization. Decentralized governance: Empowering local institutions and allowing provincial voices to influence security and development decisions would reduce the perception of Kabul as an imposition. Broad engagement: Genuine negotiations with non-Taliban political actors, civil society groups, and community elders could build a wider buy-in for national policies.

Conclusion

Afghanistan’s ethnic map is its reality; governance must be structured around that reality if peace is to be durable. The current interim regime’s heavy concentration of leadership from Pashtun heartlands, combined with an undemocratic decision-making culture, has widened existing fault lines and diminished the prospects for inclusive nation-building. Recognizing the multiethnic nature of Afghan society and translating that recognition into representative institutions and policies is not merely an ethical choice; it is a strategic necessity. Until power in Kabul reflects the full diversity of the Afghan people rather than the narrow ascendancy of one bloc, claims to national unity will remain fragile and contested.

Also Read: Border Clashes Expose Afghanistan’s Betrayal of Pakistan’s Historical Support