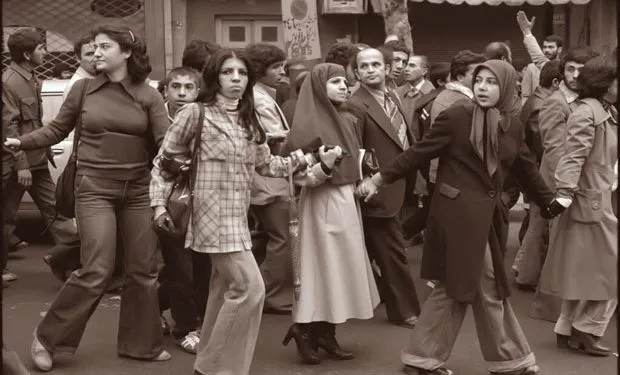

The Islamic Republic of Iran faces a severe demographic and political reassessment driven by the growing assertiveness of its women and youth in the context of persistent authoritarian governance. While more than half of the population is women and similarly, more than half of the population is youth, thus making the latter group an actual demographic majority, the foundations of Iran’s political order are being contested increasingly from within society itself. These groups are not simply reacting to episodic crises but voicing demands for political inclusion, social justice, and institutional reform that are unmistakable and sustained. Over the past few years, particularly from 2025 onward, women and youth have become the locus of Iran’s emerging political landscape, through which demographic weight has been mobilized as political agency, while the boundaries for dissent, legitimacy, and reform have been critically reconstituted within the Islamic Republic.

Demographic trends are indicative of a paradigm shift in Iranian society. The birth rate has plummeted from 6.5 per Iranian female in 1980 to less than replacement levels as of 2023, with indicators pointing towards Iranian urbanization, education for Iranian females, and Iranian social values. This has led to the Iranian “youth bulge” with 60% Iranians aged 29 years old or less, as well as Iranian women no longer submitting to Iranian social norms and authoritarian politics. Nevertheless, inherent inequities continue to exist. Despite a near equality of levels of education achieved, a majority of Iranian graduates being women, their integration with the labor force is surprisingly small, with no more than 13% of them being active members of the labor force by 2025, one of the lowest within the ME. Such a phenomenon of women being highly educated and yet inactive within society not only underscores inherent discrimination, but also contours that of political discontent motivating wider societal movements. The political institutions of Iran also represent gender disparities. Although the Iranian Islamic Republic’s constitution does not prevent women from participating in politics, there are certain limitations to their representation in major decision-making positions. The number of women in administrative positions in government has risen in the past few years, and certain advances have been made in gender equality in appointments.

The Women, Life, Freedom movement, which began in September 2022 in response to the death of Mahsa Amini in morality police custody, has become a defining feature of women’s resistance in Iran. What began as a protest against the mandatory hijab law has grown into a wider critique against state repression and a demand for a fundamental transformation of the political system. Over the past three years, this movement has not disappeared but has instead transformed into a scattered moral opposition to the theocratic regime through symbolic acts of resistance. In the early part of 2025, there were reports that women were leading the rallies in several provinces in opposition to economic concerns as well as institutionalized gender bias. Such rallies make it clear that the activism among Iranian women is not limited to the symbolic defiance against dress restrictions.

The importance of women as leaders in such protests has come into sharper relief in recent mass protests occurring in Iran as of late December 2025, first off based on economic downturns, then escalating into demands for transformative change. It is no small thing that women and young dissidents have played such a crucial role in keeping the momentum of protest going. Nevertheless, such mobilizations have also been accompanied by levels of violence unprecedented at least since the early days of democratization and independence almost two and a half decades ago. According to reports by human rights organizations, there have also been mass arrests and a large death toll, with some reports indicating that at least thousands have lost their lives as a result of protests during the early part of 2026. Globalization and the acquaintance with the outside world have transformed the Iranian youngsters into a group that is more indirectly challenging the dictatorial rule and less supportive of the clergy’s power based on religion. Surveys and independent reports suggest that large groups among Iranian youth, especially in urban centers and among the better educated, regard the imposition of religious dictates as repressive. Studies of political preference, conducted anonymously, reveal growing support for secular government and structural change, especially among younger Iranians who reject the clerical establishment’s monopoly on political authority.

The influence of social media has widened the political engagement of the younger generations, enabling the growth of counter-stories, coordinating the events, and reaching beyond the borders of the cities. Iranian youth have been utilizing such networks to resist government narratives, to report government repression, and to connect with international movements calling for democratic rights. Limitations of censorship and blackouts try to cover such networks; nonetheless, young networks find ways to keep in touch as a part of their being effective. Since the youth of Iran are very numerous and aware of technologies, they are the main positive change makers in the country. The dissatisfaction caused by the weak economy, corruption, and oppressive social norms is not only the issue of the youth group but rather a whole society that is ready for radical changes in Iran and even more.

Iran is at the moment going through a very important time in its social and political history marked by women’s rights and young political activism. Both of these sections of society represent a demographic united in their attack on the legitimacy and future of a religious regime. Both reactions have a positive vision invested in their activism. Despite repressive measures that include widespread arrests and suppression of internet communication, the fact that women and youth remain visible in large numbers on the street indicates that state violence does not and cannot quell strong demands for justice and representation. The moral language created by movements such as “Woman, Life, and Freedom” and youth politics has penetrated popular consciousness and overturned previous notions of obedience and hierarchy. However, the process of turning activism into political change is not without challenges. The Iranian government’s security apparatus, the constitutional framework, as well as its control over the electoral process, offer limited avenues for political change. The government has characterized opposition as foreign influence in an attempt to delegitimize the opposition within Iran. The process of resistance through demonstrations and symbolic gestures represents a significant shift in Iran’s political culture. Iran’s women and youth have established a new discourse in politics, suggesting that legitimacy is not derived from being religiously correct but also from the will of the people and rights-based politics.

The relationship between demographic shifts and political activism suggests that the future of the Iranian political order will be shaped in important ways by the activism of women and youth. Their activism contests the existing order of authority and offers a vision of political change based on dignity, equality, and participation. Although there is indeed to be contested and repressed, the combined demographic strength of these groups indicates the potential for building a more inclusive and responsive Iranian political framework.