A man lying in the quiet shadows of his final days, the weight of illness pressing against his body, yet no weakness touching his voice, spoke as if the very soul of the nation still surged through him. The room was hushed. Those present leaned in, for when he said, it was never merely words, but history being etched.

“Pakistan,” he began, his tone unshaken, “is a living reality.”

He paused, not from fatigue, but to let the truth settle like stone in still water. Then, with eyes brightening as if they caught the light of an unseen horizon, he said:

“When I feel that my nation is free today, my head bows in humility… This is the Will of the Almighty, this is the spiritual blessing of the Holy Prophet (peace be upon him), that the nation which the British Empire and the Indian capitalists conspired to erase is today free. It has its constitution… This is the very Khilafat that Allah promised to His Messenger PBUH, that if your Ummah chooses the straight path, We shall grant them dominion over the earth. The safeguarding of this great blessing from God is now the duty of the Muslims.”

These are not the frail utterances of a man departing the world, but the unyielding testament of one who had seen the impossible made real. Recorded by Colonel Ilahi Bakhsh and Dr. Riaz Ali Shah in Quaid-e-Azam Ke Akhri Ayyam, they stand as the heartbeat of a vision. And so begins the story of the vision behind Land of the Pure, born in the concept of khilafah and state-level implementation, upheld by faith, and entrusted forever to the courage of its people.

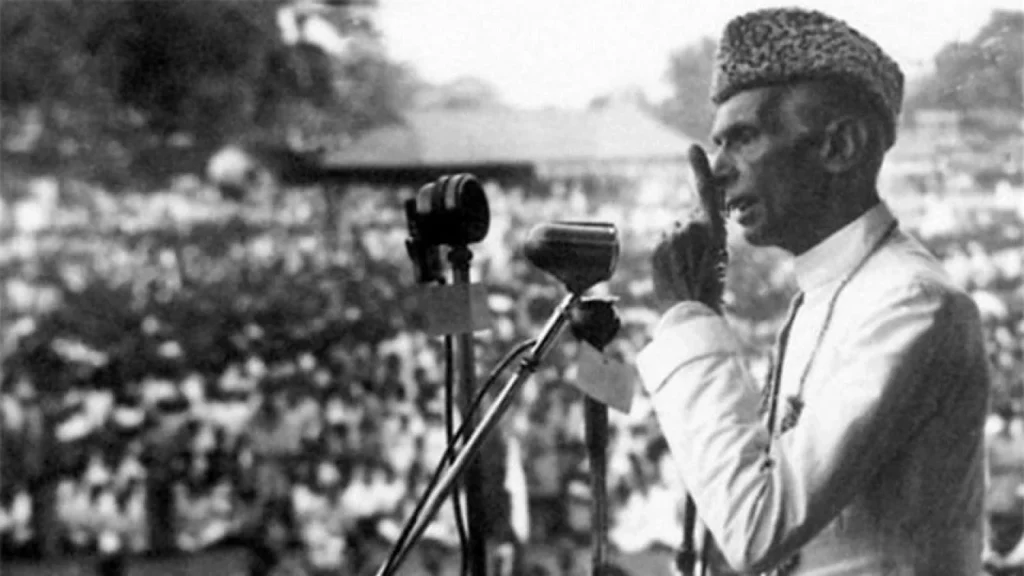

But, in the landscape of Pakistan’s history, few topics have been as misunderstood, or deliberately distorted, as the vision of its founder, Quaid-e-Azam Muhammad Ali Jinnah. A recurring myth, perpetuated by some ill-informed voices, insists that Jinnah desired a secular Pakistan, often pointing solely to his August 11, 1947 speech as evidence. Yet, as Dr. Chaudhry Ahmed Saeed in Trek to Pakistan meticulously documents, this is a distortion of both historical fact and of the Quaid’s lifelong convictions.

While addressing the Constituent Assembly on August 11, 1947, Jinnah indeed outlined the greatest challenges facing the newborn nation: maintaining law and order and safeguarding the lives, property, and religious beliefs of all citizens. This was an assurance to minorities and a call for unity, not a declaration of secularism. As Dr. Saeed notes, “Some argue it signaled a secular state, but as Shariful Mujahid observed: ‘Does one morsel make a dinner? Does one swallow make a summer?’

The speech, far from being censored, as some allege, was widely reported. Dawn (Delhi) headlined: “Jinnah Assures Minorities for Full Citizenship and Asks for Cooperation”. Pakistan Times declared: “Jinnah’s call to concentrate on Mass Welfare; Hope for End of Hindu-Muslim Distinction in Politics; Equal rights for all citizens in Pakistan State.” The Times (London) titled it: “A Call for Tolerance.”

In 1949, S.A.R. Bilgrami called it “Jinnah’s Charter of Minorities Announced.”

As Hector Bolitho, his biographer, beautifully summed up, “The words are Jinnah’s, the thoughts and beliefs are of the Prophet who said it 13 centuries earlier.”

Economic Vision

Jinnah’s vision for Pakistan was rooted in Islamic principles, not in the Western notion of secularism. On the economic front, Dr. Saeed records that the Quaid had “a very clear and vivid picture of the economic aspect of his Pakistan. There would be no place for exploitation of the common man by any group of society… He reminded them that they had forgotten the lesson of Islam: ‘There are millions and millions of our people who hardly get one meal a day. Is it civilization?’ He made it categorically clear that if this was the aim of Pakistan, he would not have it.”

While inaugurating the State Bank of Pakistan on July 1, 1948, Jinnah rejected both capitalist and communist models, urging the creation of

“an economic system based on the Islamic concept of equality of mankind and social justice.”

He envisioned narrowing the gap between “the haves and the have-nots” and evolving “banking practices compatible with Islamic ideas of social and economic life.” This was not the rhetoric of a secularist, but the blueprint of a leader seeking to anchor Pakistan in Islamic social justice.

Minority Rights

His commitment to minority rights was equally Islamic in origin. In his exchange with Lord Mountbatten on August 14, 1947, Jinnah rebutted the notion that religious tolerance began with Emperor Akbar:

“It dates back thirteen centuries ago when the Holy Prophet (PBUH)… treated the Jews and Christians… with the utmost tolerance and regard and respect for their faith and belief.”

Department Of Islamic Reconstruction:

The Quaid’s Islamic state was to be modern, just, and free from ethnic or racial prejudice, an ideal shared by Allama Iqbal and, significantly, by Muhammad Asad, the Spanish-born Muslim intellectual whom Jinnah personally invited to Pakistan. Contrary to the misconception that Islamization began under General Zia-ul-Haq, it was under Jinnah that the Department of Islamic Reconstruction was established. Its mission: to devise an enlightened framework for embedding Islamic principles into Pakistan’s governance.

Asad, a Jewish convert to Islam, delivered seven visionary talks on Radio Pakistan under the title “Calling All Muslims.” These speeches addressed the challenges Muslims faced under colonialism and urged them to transcend narrow nationalism in favor of a unified Ummah. On August 18, 1948, the department submitted a memorandum titled “Enforcement of Shariah in Pakistan” to the federal government. Its work was to be organized into four sections: Research, Education, Propaganda and Reform, and Legislative Reform.

This institutional effort, tragically cut short after Jinnah’s death and Asad’s later exile, was the purest expression of Pakistan’s founding vision: a state guided by Islamic ethics, committed to justice, equality, and the welfare of all its citizens.

Today, when the August 11 speech is torn from its context and weaponized to paint Jinnah as a secularist, we must return to the historical record. The Quaid’s words, deeds, and policies reveal a leader striving to create “an Islamic, human, and modern Pakistan ruled by justice, where all would be equal before the law regardless of religion, colour, or caste.” To claim otherwise is not just to misunderstand history, it is to misunderstand the man himself.

Also Read: Defiance: A Sinking Ship That Learned to Sail – Pakistan’s Journey Against All Odds (1947–2025)