Some artifacts remain buried beneath the rubble, and some golden pages lie hidden under the dust of time in the alley of an underground library. Lanterns hang upon the walls, long devoid of oil, their glass darkened by dust and black smoke, testifying to a once-royal glimmer. The chair near the towering shelves whispers of the owner’s lost glory, while the Moroccan leather bindings, worn yet dignified, stand as silent witnesses to the wealth of old, indeed, to a royalty long past, or an obsolete reign.

There, spirits of forgotten alleys stir once more; leaves of the leather-bound book turn at the breath of some history devotee, and the magnificent words upon those pages resurface in this digital world, where the debates of “Ronaldo or Messi” have replaced “Jarir or Farazdaq” (famed Arab poets, whose anecdote we shall meet at the end).

The air blows again, and the magic turns the leaves to the chapter of legends, who, like books, remain overlooked, like al-Muhallab ibn Abī Ṣufra, a man often ignored in the history of the subcontinent. In the dim corridors of memory, overshadowed by other conquerors, his early steps of Islam in this land remain forgotten. Yet he was the hero against the Kharijites, and the bridge between the Arabs and the Ajam, Persia, Khurasan, and Sind.

They say that history is the first identity of a region. It is often claimed that the story of Islam in the subcontinent begins with the advent of Muḥammad ibn Qāsim. But the truth is: al-Muhallab ibn Abī Ṣufra set foot in today’s Pakistan nearly half a century before Ibn Qāsim. Pakistan’s story, in spirit, begins the day the first preacher or conqueror entered this land to propagate Islam.

Muslim traders had already reached these coasts during the reign of the Righteous Caliph ʿUmar ibn al-Khaṭṭāb (may Allah be pleased with him), and continued to do so under the other Rāshidūn Caliphs. Later, in the time of Amīr Muʿāwiya ibn Abī Sufyān (may Allah be pleased with him), al-Muhallab crossed the Khyber Pass into what is now Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, advancing towards Kabul, then turning south along the Indus. From Multan to Qallat, he traced his expedition, and in doing so, inscribed what may rightly be called the first chapter of Pakistan Studies in the subcontinent, if one views Pakistan as an ideological and spiritual entity.

The Subcontinent: Where Civilisations Were Kneaded

This, however, does not deny the deeper heritage of Pakistan in the ancient civilizations of this soil, nor the enduring significance of indigenous culture. Shalwar qamīṣ, for instance, was already the dress of this region before the advent of Islam, and remains preserved to this day. What truly evolved was religion, like water, taking the shape of the subcontinent’s vessel, kneaded into its soil alongside other elements of history and culture.

The First Muslim ‘Expedition’ in the Subcontinent

The Khyber Pass became the second path trodden by Muslim horses into the lands of Khyber and Sindh (present-day Pakistan). The first was their arrival on the Makran coast, although it was through trade, not conquest; the third was their approach from the Sindh coast. But it was in 44 AH / 664 CE that al-Muhallab ibn Abī Ṣufra entered this land in earnest. His advent is recorded in nearly all classical Islamic chronicles, Futūḥ al-Buldān, Tārīkh al-Ṭabarī, and al-Kāmil fī al-Tārīkh of Ibn al-Athīr, among others. Orientalists, too, have taken note of it. Andre Wink, in his Al-Hind: The Making of the Indo-Islamic World, writes:

“In the era of Amīr Muʿāwiya, when ʿAbdullāh ibn ʿAbd al-Raḥmān and al-Muhallab ibn Abī Ṣufra were engaged in battle against the Kabul Shahi dynasty in the regions of Zabul and Kabul, it was in that very time, in the year 664 CE, that al-Muhallab pressed forth from Kabul, passing through Bannu, Lahore (Swabi), until he reached Multan.”

The Urdu Encyclopedia of Islam likewise records that when Rājā Chach (father of Rājā Dāhar, about whom the Chachnāma was later written) conquered Multan, it was only four years after his death that al-Muhallab reached the city in 664 CE. In the same year, Muslims had also taken Sajistan and Makran. Multan Fort itself, however, remained unconquered until the time of Muḥammad ibn Qāsim.

Al-Muhallab’s march led him from Lahore (Swabi) to Bannu (recorded as Banna بنۃ in Arabic texts), and thence along the Indus towards Multan.

Life and Personality of Al-Muhallab

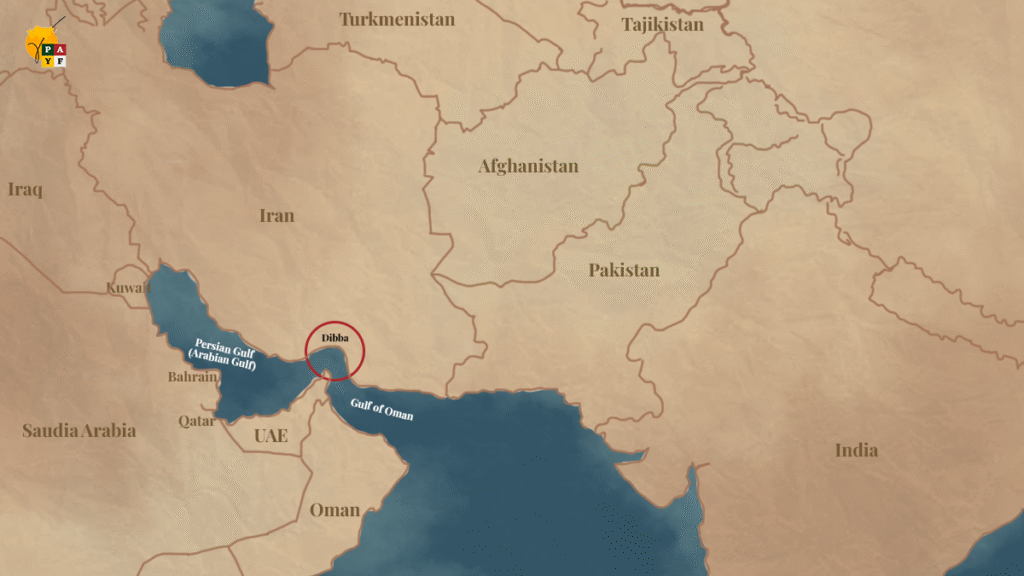

Al-Muhallab was born in 629 CE to Zālim ibn Suraqah, known as Abū Ṣufra, two years before the Prophet’s ﷺ passing in 632 CE. Thus, he was not a Companion but a Tābiʿī. He encountered ʿUmar ibn al-Khaṭṭāb and other noble Companions. Indeed, ʿUmar once called him “the best among his brothers” (al-Iṣābah fī Tamyīz al-Ṣaḥābah, al-ʿAsqalānī, p. 205). He was born in Dabba (present-day Dibba, Oman), near the Strait of Hormuz, so close to Gwadar that it can be sighted without aid.

Al-Muhallab had two wives and eight children, seven sons and one daughter. All proved capable commanders. His daughter, Hind bint al-Muhallab, was married to al-Ḥajjāj ibn Yūsuf, though the marriage ended in separation. He also narrated a few ḥadīth.

Yet the most glorious chapter of his life was his seventeen-year struggle against the Kharijites. He crushed them with wit, patience, and valour. An erudite general, he knew their false doctrine well and fought them with intellect as much as with the sword. History has preserved this struggle in full magnificence. For his brilliance in leadership and administration, he was appointed governor of Persia, Mosul, Armenia, Azerbaijan, and Khurasan.

He was an optimist, deeply grateful. When he lost one eye in battle, he thanked Allah that the rest of his body was spared, and that blessing was enough to make him forget the loss. Among his words of wisdom were:

“The best sitting or assembly is that in which vision broadens, and in which the benefits for those present increase.”

Al-Muhallab embodied the principles of Islam in politics as well. He fought beside ʿAlī ibn Abī Ṭālib against the Kharijites, and after ʿAlī’s martyrdom, gave allegiance to Amīr Muʿāwiya. During Muʿāwiya’s reign, he campaigned into present-day Pakistan. But he refused to support Yazīd ibn Muʿāwiya, instead pledging allegiance to ʿAbdullāh ibn al-Zubayr (may Allah be pleased with him), under whom he fought the Azāriqa and Najdat sects of the Kharijites. After Ibn al-Zubayr’s death and the Umayyad conquest of the Ḥijāz, he continued his struggle against the Kharijites under ʿAbd al-Malik ibn Marwān.

The Psychology of the Kharijites

The Kharijite mindset was extreme and reckless. They were ever eager to sow discord, and fought merely for discord. They had first declared support for ʿAbdullāh ibn al-Zubayr, but later turned against him because of his favourable stance toward both ʿUthmān ibn ʿAffān and ʿAlī ibn Abī Ṭālib. Al-Muhallab used their very psychology against them. He waged a war of minds as much as of arms. He believed firmly in the Prophet’s saying: “War is deception.”

He sowed distrust among their ranks. Once, he sent a forged letter, along with 1,000 dirhams, to an arrow-forger among the Azāriqa, reading:

“The arrows are received, payment with thanks.”

The letter was discovered, and the forger was executed by his own men without trial. Their unity fractured. At other times, al-Muhallab dispatched agents to provoke theological disputes among them. Thus, he broke them from within, as he fought them from without, a legend, drawing inspiration from the path of ʿAlī ibn Abī Ṭālib.

A Literary Interlude: Jarir or Farazdaq (anecdote)

Amidst the harsh wars with the Azāriqa, an anecdote survives, recorded in Michael Cook’s A History of the Muslim World: From Its Origins to the Dawn of Modernity. Al-Muhallab’s troops, weary of war, fell to quarreling not over strategy or courage, but over poetry. Was Jarīr the greater poet, or Farazdaq? The argument burned hot, each side defending its favourite bard. Half in jest, but mindful of his men’s passion, al-Muhallab proposed that their enemies should decide who could be more impartial than those sworn to kill them?

On the eve of battle, a soldier shouted across the field to the Azāriqa, calling upon ʿUbayda ibn Hilāl to arbitrate. ʿUbayda reproached them sternly: how could men on the brink of death trifle with poetry when divine judgment loomed? Yet, after a pause, he recited a line of exquisite verse. When the Muslims acknowledged it as belonging to Jarīr, he replied:

“Then Jarīr is the better poet.”

Thus, even on the threshold of bloodshed, the power of language prevailed, and enemies found a fleeting communion in reverence for verse. And one cannot help but wonder: how did they resume battle after such a heart-stirring exchange? Perhaps the men of that age were truly civilised, civilised enough to pause for literature, and then return to their cause.

Al Muhallab’s Death

In the year 702, in Zaghol’s dust, al-Muhallab’s journey found its rest, yet his name marched on in history’s verse.

Also Read: Mullah Din Muhammad Mushk-e-Alam: Faith, Fury, and Afghan Resistance