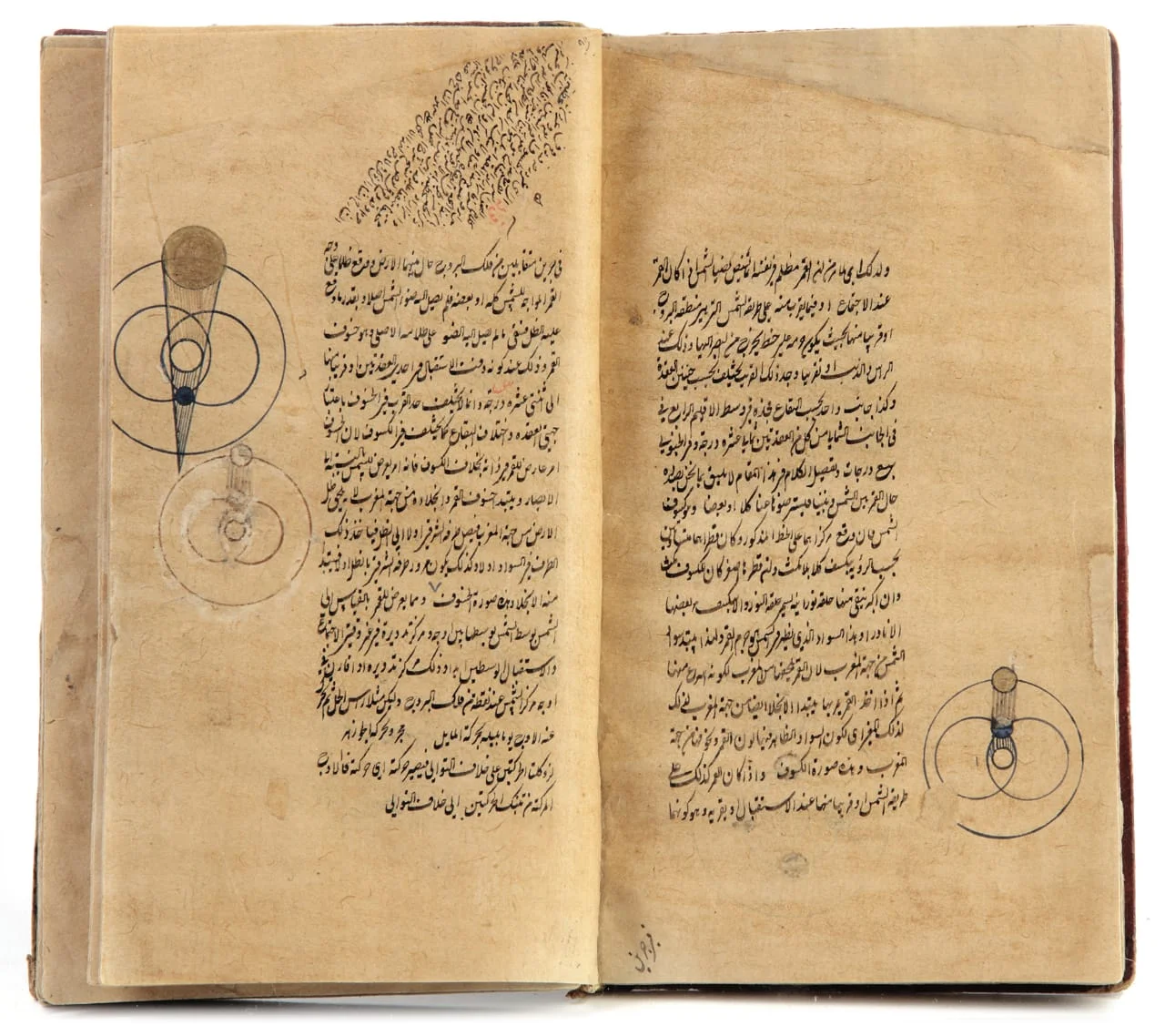

It is a curious thing to consider what made our modern ages, the Industrial and Information Ages, so profoundly revolutionary. Could it be attributed, at least in part, to a new way of seeing the world, one where the elegant language of mathematics became a universal tool for understanding and shaping reality? But who first pioneered this worldview? Perhaps it was the Muslims, through the infusion of Islamic, Arab, and Persian intellectual traditions. Infact, nearly four centuries before Fibonacci was convincing Europeans about zero, Al-Khwarizmi of Persia had already introduced it.

In a similar vein, we can look back to a legendary fusion of cultures in the distant past, where the seeds of a new scientific tradition were sown.

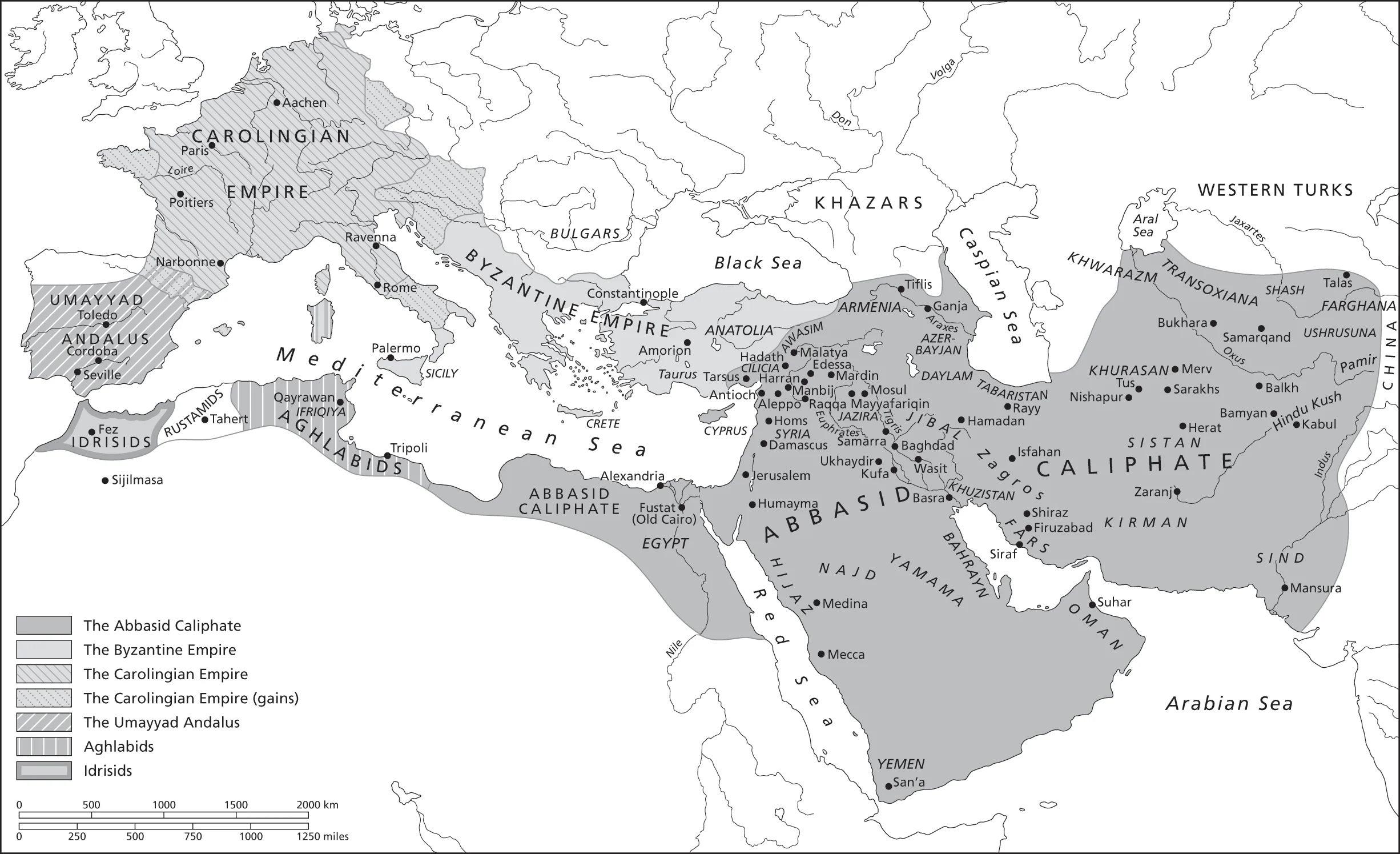

The tale of how Abbasid power reached the heart of Central Asia is, in its own way, as compelling as the very genesis of algebra. It is a story woven with the threads of ambition, revolution, and the remarkable meeting of minds that would profoundly impact the centuries to come. At its heart was the House of Wisdom in Baghdad, a crucible where the rich intellectual traditions of Persia and the burgeoning scholarly zeal of the Arab world converged, birthing a new age of discovery.

Early Steps in Central Asia(710–750 CE):

The 8th century dawned in Persia under the shadow of the Umayyad Caliphate, a vast and dominant force that had swept across the region in the preceding century. For years, Arab governors ruled the Persian plateau from Damascus, relying heavily on the local dihqans (Landed proprietors, heads of a village who held certain lands by hereditary right and were responsible for the collection and payment of the taxes (Sasanian and early Islamic periods) to manage the territories and, crucially, to collect taxes. This reliance on the established local administration created a complex, often uneasy, balance of power.

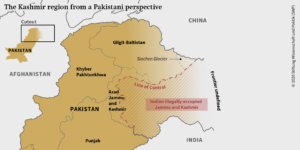

To the east, the Umayyads’ attention turned to the fabled lands of Central Asia, a mosaic of independent principalities known to the Arabs as Mawarannahr, or “what is beyond the river.” Under the relentless command of generals like Qutayba ibn Muslim, Umayyad forces systematically pushed into this heartland. In the early 710s, they conquered the wealthy merchant city of Bukhara, and after a long siege, they brought Samarqand to heel.

The tale of Qutayba’s conquest is an interesting one. During the reign of the Umayyad caliph Walid ibn Abdul Malik, he was sent to Khurasan by the governor of Iraq, Hajjaj. Qutayba conquered all of Central Asia in a short period of time, in 710-715, and managed to send ambassadors to the Chinese emperor.

A famous anecdote is that after some time, when Umar bin Abdulaziz ascended the throne, and Arabs in Bukhara were ordered to move, the residents objected to the decision to resettle the Arab families who were moved to Bukhara and other big cities to maintain stability in Movarunnahr, and expressed that they were satisfied with their life with the Arabs. This shows the magnificence of Islamic civilisation and its impact on the locals there.

According to the story of “Ad-Dawlatul Umawiyya”, the Muslim troops led by Qutayba ibn Muslim al-Bahili directly conquered Samarkand, without first offering the local population a choice between accepting Islam, making a treaty, or going to war. After the locals learned that this was against Islamic law, they sent a letter of complaint to the caliph. Khalifa transferred the consideration of this case to the judge.

The judge ruled that Qutayba and his people should leave Samarkand. This was the first verdict in the history of the world that the victorious people’s judge issued in favor of the defeated people. Qutayba and his soldiers apologized to the people of Samarkand and left the city . Seeing this, most of Samarkand’s population converted to Islam.

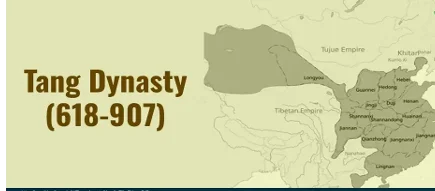

However, there was another formidable power in the east at that time, the emperors of modern-day China; therefore, this period was also marked by fierce resistance from the local Soghdian rulers, as well as the powerful Turkic and Tibetan empires, who vied for influence in the region. The conquests were not easy or permanent; they were a series of raids, occupations, and hard-won battles.

Tidbit:

Mavrannahr (ما وراء النهر) literally means “the land beyond the river” and historically referred to Transoxiana (the region beyond the Oxus/Amu Darya River, covering parts of modern Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, southern Kyrgyzstan, and southwest Kazakhstan).

The Abbasid Revolution and the Winds of Change

By the mid-8th century, a storm was brewing, and the religio-political rising that overthrew the Umayyads, who had power in Damascus, began in Persia, in the province of Khurasan. This was the ‘Abbasid Revolution. It would be a brave man who would attempt to explain that revolution in a few lines; there are many explanations being presented for this. It has been thought of as a movement of Persians versus Arabs, and one of some Arab tribes against others, or as one of some Arabs plus some Persians against other Arabs.

The Abbasid family, a rival clan tracing its lineage to the Prophet Muhammad’s uncle, masterfully capitalized on the frustration or differences. They sent a charismatic Persian general, Abu Muslim of Khurasan, to lead a revolutionary movement. It was here, in the province of Khurasan, a region with a deep reservoir of Persian identity and a mix of Arab and Persian inhabitants, that the revolution exploded in 747 CE.

Abu Muslim’s army, a potent coalition of disgruntled Arabs and motivated Persians, marched west, sweeping aside Umayyad resistance. The revolution, in its complexity, was a momentous turning point. It signaled a new era where Persian influence would re-enter the corridors of power on a scale not seen since the fall of the Sasanian Empire.

However, too much reliance on the Khurasanis was soon seen to be potentially dangerous. In 755, the excessively influential Persian architect of the ‘Abbasid Revolution, Abu Muslim, was murdered. Serious revolts promptly broke out in Khurasan, and in later troubles, rebel leaders sometimes claimed to be the “real” Abu Muslim. In the 830s, the caliph al-Mu’tasim decided that radical measures were necessary and that the whole basis of recruitment of the ‘Abbasid army should be changed. This was when the caliphate decided to appoint Turkish slaves to the military, which we have talked about in the last episode.

A New Caliphate in an Old Heart

The victory of the Abbasids was not merely a change of dynasty; it was a fundamental shift in the very soul of the Islamic empire. The new caliphs, brought to power by a Persian-led army, moved their capital from Damascus to the newly founded city of Baghdad in 762 CE. This move was symbolic and significant. Baghdad was not just a new city; it was built near the ancient Sasanian capital of Ctesiphon, re-establishing the imperial center in the heart of Mesopotamia.

The Abbasid court embraced a new, more stately demeanor. While the Umayyad caliphs had often maintained a “more accessible”, almost tribal, presence, the Abbasid rulers adopted the elaborate court ceremonies and customs of the ancient Persian emperors. They became distant and revered figures, approached only with a formal ceremony, a transformation from a tribal chief to a true “Oriental monarch.” This Persian flavor was also evident in the administration, where a new office, the vizier or chief minister, rose to prominence, a role with “roots in the Sasanian bureaucracy.”

A Golden Age of Minds and Trade

The Abbasid era ushered in a period of unprecedented intellectual and commercial flourishing. The empire’s reach, from Spain to Central Asia, created a vast, interconnected trade zone. The Caliphate actively promoted this trade, building caravanserais (rest houses), and financing the construction of bridges and roads that improved ancient routes like the Silk Road.

This flourishing trade went hand-in-hand with an explosion of knowledge. The Abbasids avidly patronized learning and scholarship. The House of Wisdom in Baghdad became the central repository for ancient knowledge, where Greek, Indian, and Persian texts were painstakingly translated into Arabic. It was within this environment that minds from across the empire, particularly from the Persian heartland of Central Asia, would make groundbreaking contributions.

One such luminary was Abu Hanifa (699–767 CE), a Persian scholar who founded the Hanafi school of jurisprudence. His methodical and rational approach to Islamic law would make his school one of the most influential and widely followed in the Islamic world.

Another giant from the region was Muhammad ibn Musa al-Khwarizmi (c. 780–850 CE). Though his most famous works were written just beyond the 8th-century mark, his foundational education was in the late 8th century, and he represents the brilliant tradition that was taking root. It was al-Khwarizmi who introduced the world to algebra and standardized the use of Hindu-Arabic numerals, including the number zero.

A Legacy Set in Stone

The 8th century was a transformative period for Persia and Central Asia. It began with the region under the military and administrative control of the Umayyad Caliphate and ended with it at the heart of a new, culturally syncretic Abbasid empire. The rise of this new power was a revolution born of social and political unrest, but its legacy was an intellectual and cultural one.

The Battle of Talas in 751 CE was a final, critical turning point. Here, Abbasid forces defeated the Tang Dynasty, cementing Islamic control over Central Asia and bringing about a momentous cultural exchange. Among the spoils of war were Chinese artisans who had the secret of papermaking, a technology that would soon spread across the Islamic world, accelerating the spread of knowledge and setting the stage for the coming Golden Age.

The fusion of Persian tradition and Arab governance, along with the thriving intellectual spirit, ensured that Central Asia would not merely be a conquered territory but a vital wellspring of innovation and scholarship for centuries to come.