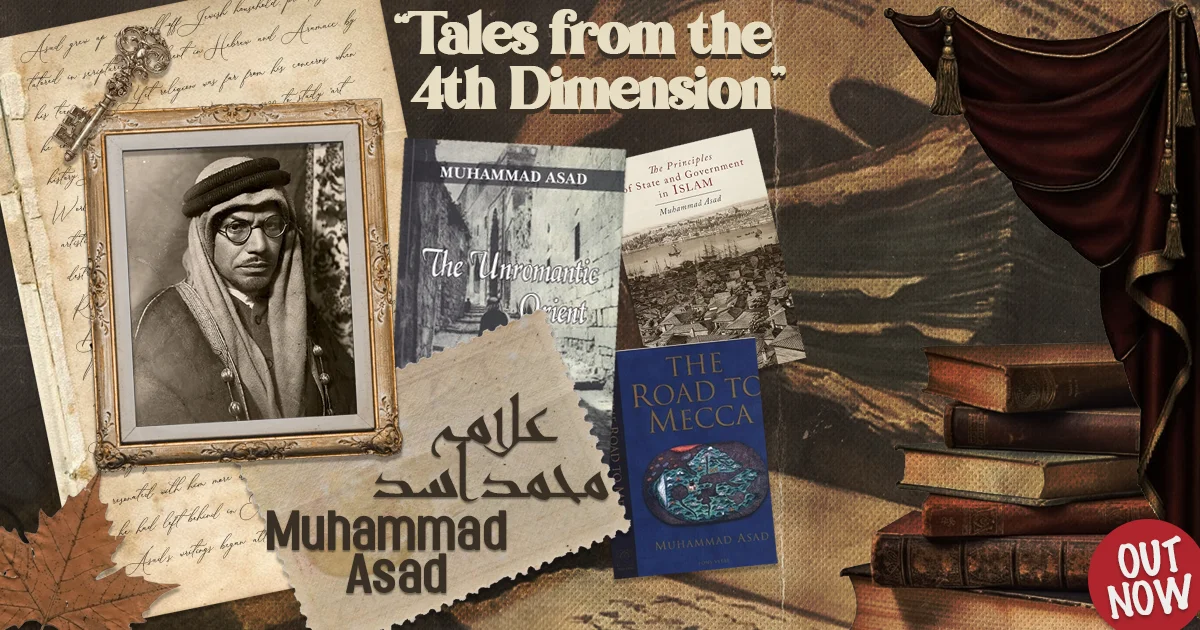

Born in 1900 as Leopold Weiss to Jewish parents in the city of Lwow, then part of Austria, Muhammad Asad’s extraordinary journey carried him from Europe’s war-torn landscapes to the deserts of Arabia and finally to the heart of Pakistan’s intellectual and political life. By the time of his passing in 1992, he was celebrated as a foremost Muslim intellectual, author of The Road to Mecca, and the holder of Pakistan’s first passport.

Early Years and Search for Meaning

Asad grew up in a well-off Jewish household, privately tutored in scriptures and fluent in Hebrew and Aramaic by his teenage years. Yet religion was far from his concerns when he entered the University of Vienna in 1920 to study art history. Like many young Europeans in the aftermath of World War I, he drifted through Vienna’s literary and artistic circles, searching for meaning in a continent scarred by destruction and disillusionment.

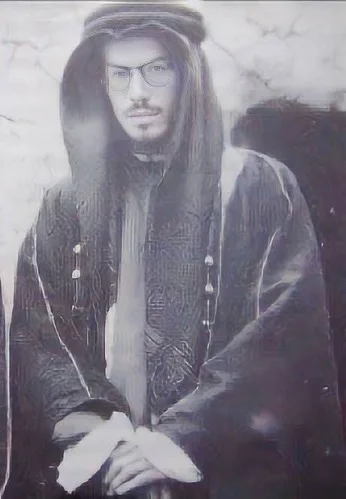

Restless and estranged from academia, Asad moved to Berlin, working briefly as a journalist before traveling to Mandatory Palestine in 1922. There, amid political upheaval and the rise of Zionism, he found himself drawn not to Jewish nationalism but to the simplicity of Arab life. The honesty of the Bedouin and the spiritual vitality of Islam resonated with him more deeply than the decayed moral order he had left behind in Europe.

By 1926, Asad had formally embraced Islam, taking the name Muhammad Asad. It has been alleged that he had embraced Islam in the hands of Maulana Sadr ud din, Imam of Berlin Mosque run by Lahore Ahmediyya Movement. However, the veracity of this claim is not unquestionable. His fascination with the Arab world soon became devotion, leading him to spend years in the deserts of Arabia, where he developed a deep command of Arabic and grew close to King Ibn Saud.

Intellectual Contributions and Encounters

Asad’s writings began attracting attention in Europe. His articles in the Frankfurter Zeitung, later compiled as The Unromantic Orient, painted the Arabs as a people of resilience and authenticity. He became increasingly concerned with the political fate of Muslims, confronting Zionist leaders such as Chaim Weizmann and defending Palestinian rights long before such positions gained international attention.

During his travels across the Arab world, Asad met many influential figures, including resistance leaders. In Libya, he encountered Omar Mukhtar, the legendary “Lion of the Desert,” who was leading a valiant struggle against Italian colonial rule. The meeting left a deep impression on Asad: here was a man embodying courage and sacrifice.

In India during the 1930s, he encountered the poet-philosopher Allama Iqbal, who profoundly influenced his thought. Iqbal urged Asad to abandon his wanderings and devote himself to the intellectual groundwork of a future Islamic state. Their conversations shaped Asad’s conviction that Islam offered not only a faith but also the basis for a just political order.

Asad contributed to the Pakistan Movement through lectures, articles, and the founding of his periodical Arafat, in which he argued that Pakistan was not to be merely a refuge for Muslims but a state dedicated to realizing Islamic ideals in politics, law, and society.

Pakistan and State-Building

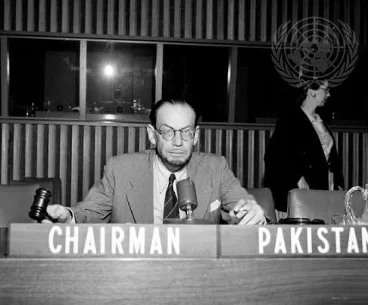

After the Partition, Asad settled in Lahore. At the invitation of Punjab’s Chief Minister, he established the Department of Islamic Reconstruction in 1947, the first official institution in Pakistan explicitly tied to Islam. Soon after, he joined the Foreign Service, becoming Deputy Secretary in charge of the Middle East Division. Carrying the very first passport stamped “Citizen of Pakistan,” Asad toured Arab capitals to explore the possibility of forming a league of Muslim nations. His plans collapsed with the assassination of Prime Minister Liaquat Ali Khan.

Later, Asad served as Minister Plenipotentiary at Pakistan’s Mission to the United Nations. Yet his independent spirit and strained relations with colleagues pushed him out of government service. During this period, he produced some of his most influential works, including The Road to Mecca and The Principles of State and Government in Islam.

Later Years and Legacy

Although sidelined from official posts, Asad remained intellectually engaged with Pakistan. He was invited back under General Ayub Khan to advise on constitutional matters, and again by General Zia-ul-Haq in the 1980s. True to his vision, he argued consistently for an inclusive interpretation of Islam, insisting, against prevailing orthodoxy, that Muslim women had equal political rights, even to the office of Prime Minister.

Muhammad Asad’s writings influenced thinkers across the Muslim world. Sayyid Qutb of Egypt drew upon his works, while Margaret Marcus, a Jewish American, converted to Islam after reading The Road to Mecca and became the scholar Maryam Jameelah. Though he spent much of his later life abroad, Asad cherished Pakistan as the embodiment of Iqbal’s dream and his own intellectual labor. He was its first citizen.

Towards the end of his life, Asad moved to Spain, where he lived with his third wife, Pola Hamida Asad, an American national of Polish Catholic descent who had also converted to Islam. He remained in Granada until his death on 20 February 1992, at the age of 91. He was laid to rest in the Muslim cemetery of Granada, in Andalusia, a fitting resting place for a man whose life had bridged East and West, and who cherished the memory of al-Andalus as a symbol of Islamic civilization’s intellectual and cultural vitality.

Talal Asad: An Intellectual Legacy Continued and Gen-Z Resonance

Muhammad Asad’s son, Talal Asad, went on to become one of the most influential anthropologists of the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries. His work on secularism, colonialism, and the anthropology of religion has shaped debates in universities across the globe. Building on the intellectual courage of his father, Talal examined how concepts of religion and power are intertwined in modern societies. His work continues to enjoy popularity among Gen-Z and Millennial readers, and on digital forums and social reading platforms, his words are frequently quoted by young Muslims

Conclusion

Muhammad Asad’s life was a bridge between worlds: between Judaism and Islam, Europe and Arabia, philosophy and faith. In Pakistan’s formative years, he offered both scholarship and vision, seeking to root the state not in ethnicity but in Islamic ideology. His works and legacy endure, marking him as one of the intellectual founders of Pakistan.

Also Read: The Overlooked General: Al-Muhallab and the Dawn of Islam in South Asia