Building on our last discussion about the generic prehistoric and historic eras of Asia, we now delve into the magnificent saga of Persia. In this article, we will explore the annals of its ancient glory, witness its dramatic transformation into a new era of Islamic rule, and uncover the wisdom with which its rich heritage was not only absorbed but also preserved and celebrated.

The Death of a King, the Birth of a World: How the Fall of Persia Changed Everything

What if the world’s true center was never Rome, nor a distant corner of Europe, but a powerful, elegant empire at the heart of the Silk Roads? What if the most pivotal military engagement in history was not fought on the fields of a Greek or Roman battlefield, but in the fertile lowlands of ancient Iraq? This is the story of a monumental clash of civilizations, not just between two armies, but between an old, decaying world and a new one waiting to be born. It is the story of how the demise of a Persian king in the 7th century CE irrevocably altered the course of human history, a moment meticulously foretold by the philosophical currents of its time.

I. The Achaemenid Legacy: A Foundation of Power

The history of pre-Islamic Persia is a long and storied tapestry, defined by successive periods of power. The first of these great empires was the Achaemenid Empire (550–330 BCE), founded by Cyrus the Great. At its height, it was the largest empire the ancient world had ever seen, ruling over 44% of the world’s population. After it fell to Alexander the Great in 330 BC, Persian culture and influence were sustained by the Parthian Empire for nearly 500 years, a powerful entity that rivaled the Roman Empire. This long legacy set the stage for the final pre-Islamic Persian dynasty: the Sasanians.

II. The Sasanian Empire: The New King of Kings

The Sasanian Empire (224-651 CE) was the last pre-Islamic Persian state, a civilization that consciously sought to restore the glory of the Achaemenid era. For four centuries, it reigned as a true superpower, a rival to Rome and Byzantium, and the undisputed master of the Eurasian heartland. Its society was a marvel of organization, built around a powerful monarch, the

Shahanshah or “King of Kings,” who presided over a centralized state with a sophisticated bureaucracy and a robust taxation system.

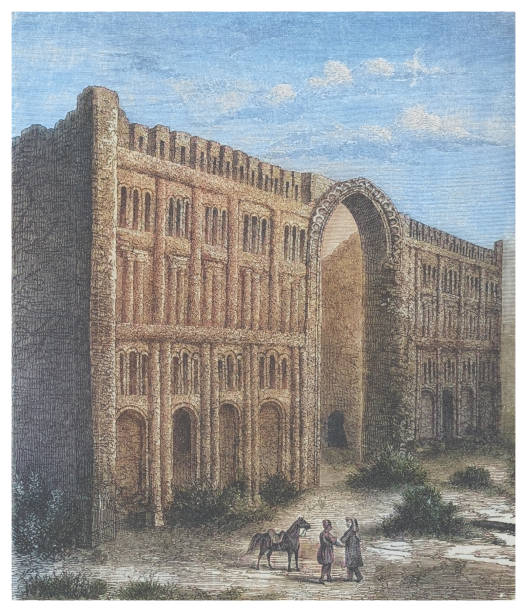

Militarily, the Sasanians were a formidable force. Their army was a blend of disciplined infantry and elite, heavily armored heavy cavalry known as the Asvaran, a unit so effective that both Byzantine and Islamic powers later emulated its strategies. But the empire’s power was not merely military; it was a cultural and economic juggernaut. It controlled and profited from crucial sections of the Silk Roads, a network of trade that funneled immense wealth and influence from East to West. From its architecture of domed halls and vaulted halls to its exquisite metalwork and textiles, Sasanian influence spread far and wide, laying the artistic and administrative foundations for the Islamic civilization that would succeed it.

This was a world at its zenith. But even at its height, a storm was gathering on the horizon, one that would expose the fatal paradox at the heart of this ancient power.

III. The Empire that Ate Itself

The collapse of the Sasanian Empire was not a sudden act of fate, but a long, slow decay that began with a catastrophic, decades-long war against the Byzantine Empire, which bled both empires dry of resources and manpower. The war’s end brought not peace, but a devastating civil war and a fatal dynastic purge after the execution of King Khosrow II in 628 CE. This period of profound anarchy saw power fragment among a dozen monarchs in just a few years, leaving the once-formidable state politically and economically weakened. By the time a child-king, Yazdegerd III, was crowned in 632 CE, he was a mere figurehead, with real power resting in the hands of warring aristocrats.

This internal decay was the primary factor in the empire’s ultimate fall. However, the Sasanian decline was met by a formidable adversary: the Rashidun Caliphate. The Muslim army was characterized by its superior tactical flexibility, high morale, and a potent motivation rooted in a shared faith. This powerful combination of discipline and purpose was the highest factor in their triumph. The Sasanian military, in contrast, was largely composed of war-weary new recruits. The victory of the Rashidun forces at Qadisiyyah, therefore, was a clash between an old, internally-conflicted state whose group solidarity had collapsed, and a new, cohesive force with an unshakeable sense of purpose.

IV. The Unstoppable Force Meets the Immovable Object

The stage was set for the Battle of Qadisiyyah in 636 CE. In one corner stood the Sasanian army, a theoretical titan with its elite cavalry and terrifying war elephants, but in reality, a war-weary force of recruits led by General Rostam Farrokhzad, who was a de facto ruler in a broken imperial system. In the other corner stood the Rashidun army, a smaller, less-equipped force led by Sa’d ibn Abi Waqqas. But what they lacked in numbers, they more than made up for in spirit. The Arab tribes had transcended their traditional bonds and forged a new, potent force based on the unity of Islam. This shared faith provided a common purpose and an unwavering morale, creating a cohesive, action-oriented unit.

Also the ideological superiority and spiritualism played their part. Here is a famous tale about Rostam, the great Sasanian General:

On the battlefield of Al-Qadisiyyah, Rustam was continually confounded and greatly distressed when he heard the muezzin calling out the adhan. While taking stroll, he heard the muezzin call the Muslims to perform the dawn prayers. The whole army rose and began to prepare to pray. When he saw this, Rustam immediately called on the Iranians to mount their horses. When asked the reason for this, he said, “Don’t you see that your enemy has been given the command to move against us?” His spy said, “They are moving to perform their prayer.” Rustam then said to the spy in Persian, “In the morning I heard the voice of Umar.” When Rustam heard the adhan for Thuhr, he said,

“Umar has perforated my liver.” [History of Tabari].

He mentioned the name of Umar, may Allah be pleased with him, because he believed this was the leader of the whole Muslim nation and the muezzin is his representative

Early Islamic accounts describe a brutal, four-day engagement. The Sasanian war elephants initially proved a significant problem, but the tide turned dramatically on the final day. A sandstorm is said to have blinded the Sasanian forces, and in the ensuing chaos, their commander, Rostam Farrokhzad, was killed under uncertain circumstances. His death confirmed what was already true: the Sasanian will to fight had been broken, and the state was a hollow shell. The battle itself was a decisive victory for the Rashidun forces. But its significance extends far beyond the battlefield.

V. The Dawn of a New World

The victory at Qadisiyyah left the Sasanian capital of Ctesiphon undefended. It fell after a two-month siege, a monumental event that consolidated Muslim rule over Mesopotamia and paved the way for the conquest of the Persian mainland. Although the Sasanian state lingered for a few more years, with many localities putting up fierce resistance, the Battle of Nahavand in 642 CE, often called the “Victory of Victories,” ended all organized military resistance. The final act came in 651 CE with the death of Yazdegerd III, bringing the 400-year Sasanian dynasty to an end.

The profound meaning of these events, as Peter Frankopan argues, is that they reoriented the axis of global power. The true center of the world did not shift from Rome to Western Europe, but from one axis of the Silk Roads to another. The fall of the Sasanian Empire and the subsequent rise of the Rashidun Caliphate cemented the Middle East’s role as the new political, economic, and cultural heartland of a vast intercontinental empire.

The conquest was not an act of erasure. While the state religion of Zoroastrianism lost its official status, the Sasanian legacy was gradually absorbed and synthesized into the nascent Islamic culture. As Ibn Khaldun famously noted, the great intellectual and scholarly achievements of the Islamic Golden Age were the “preserve of the Persians,” who adopted and transformed the new faith, ensuring their culture would continue to thrive and shape the world for centuries to come. The Battle of Qadisiyyah was not an end, but a transformation, a violent, cataclysmic moment that closed a chapter of history and began an even more profound one.

Also Read: Episode 1: Dynasties to Democracies: From Antiquity to the Medieval Crossroads of Asia